Diesel Shortage Raises Fears for Humanitarian Crisis in Venezuela | via: Voice of America

Alejandra Arredondo y Gustavo Ocando Alex | Washington/Maracaibo | February 9, 2021

Experts are warning of a looming humanitarian crisis in Venezuela if President Joe Biden’s new U.S. administration does not lift restrictions that are preventing the South American country from swapping its plentiful crude oil reserves for refined diesel fuel from abroad.

With Venezuela’s refinery sector in disarray after years of mismanagement, the country has become increasingly dependent on imported diesel fuel to generate electricity and transport essential goods including food, medicine and humanitarian supplies.

That international lifeline has been cut off by new U.S. sanctions introduced by the administration of former President Donald Trump last August. No diesel shipments have arrived in Venezuela since October 2020 and existing supplies are expected to run out in March.

It is not yet clear how the new White House team plans to deal with the crisis. Press secretary Jean Psaki recently said the administration wants to promote a peaceful and democratic transition in Venezuela through free and fair elections. She also said Washington will “prosecute individual” Venezuelans implicated in corruption and human rights violations.

Why is diesel important?

The gas shortage in Venezuela, caused by the collapse of the oil industry and years of U.S. sanctions, has forced the country to import diesel and gas both through bartering with companies like Repsol in Spain, Reliance in India and Eni in Italy, also importing diesel from Rosneft, the Russian oil company that was banned by the United States.

Diesel, therefore, gained relevance as the engine for essential activities for society. “It is a very important fuel for various activities that have humanitarian relevance, in particular food transportation, electricity generation and public transportation,” Francisco Rodríguez, a Venezuelan economist, explained to Voice of America.

Currently, the country has enough supply of diesel to meet the minimum demand until the end of March, said Luis Vicente León, director of Datanalisis, a consulting firm in Venezuela.

When was diesel trade banned and why?

Since October 2020, the government of former U.S. President Trump has prohibited oil companies from sending diesel to Venezuela in exchange for crude. The year before in January 2019, the U.S. imposed sanctions to PDVSA, the Venezuelan state oil company; however, diesel trade was exempt.

Repsol, Reliance and Eni participated in this exchange with PDVSA. According to Consecomercio, a private sector organization in Venezuela, not a single ship loaded with imported fuel has arrived in the country since October 24 of last year.

The former envoy of the U.S. Department of State, Elliott Abrams, justified the measure as a tool of pressure on President Nicolas Maduro, arguing that the Venezuelan government was sending crude and diesel to Cuba.

In the last three months, Venezuela sent Cuba an average of 4,000 barrels a day of diesel, according to Reuters data. Experts agree, however, the amount that is sent to the island is small, compared to what is consumed and needed.

“Shipments to Cuba are tiny compared to the diesel deficit that would be generated by breaking the agreement,” León said. The gap between the amount of diesel consumed and that demanded in the country is between 16,000 and 20,000 barrels a day, the expert said.

National diesel consumption in Venezuela is estimated at 100,000 barrels a day, according to figures published last November by the Unitary Federation of Petroleum Workers of Venezuela. Iván Freites, secretary of that union, affirmed then that PDVSA’s refineries were only producing 25 percent of what was required, that is, about 25,000 barrels a day.

A ‘humanitarian’ measure

Experts say that lifting the oil-diesel exchange ban will give Venezuela essential access to fuel and that without it, the humanitarian crisis in the country could worsen.

Miguel Pizarro, the envoy to the United Nations of Juan Guaidó, one of the opposition leaders recognized by dozens of countries, including the United States, as interim president of Venezuela, told Voice of America that the humanitarian emergency is not caused by sanctions, but he does recognize that they can have a negative impact by being in effect a long period of time.

Guaido says he also thinks that sanctions over a long period of time will have an impact.

“This sanction [on the exchange of oil for diesel], applied for a long time, could affect the distribution of humanitarian assistance in the country and the capacity to provide services,” wrote the opposition politician to VOA.

Before the U.S. government made the decision to implement sanctions, a group of 115 organizations and individuals wrote to former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, asking him not to do so.

A ‘national scale’ problem

One of the most affected sectors in Venezuela is the state of Zulia, with a high population and affluent commercial zones. Sanctions and prohibitions against PDVSA have not allowed merchant and dealers to exchange oil for diesel.

Erasmo Aliam, a labor union member in the transportation sector, highlights that the transfer of passengers, food, medicine and various cargo has been affected by the shortage of diesel.

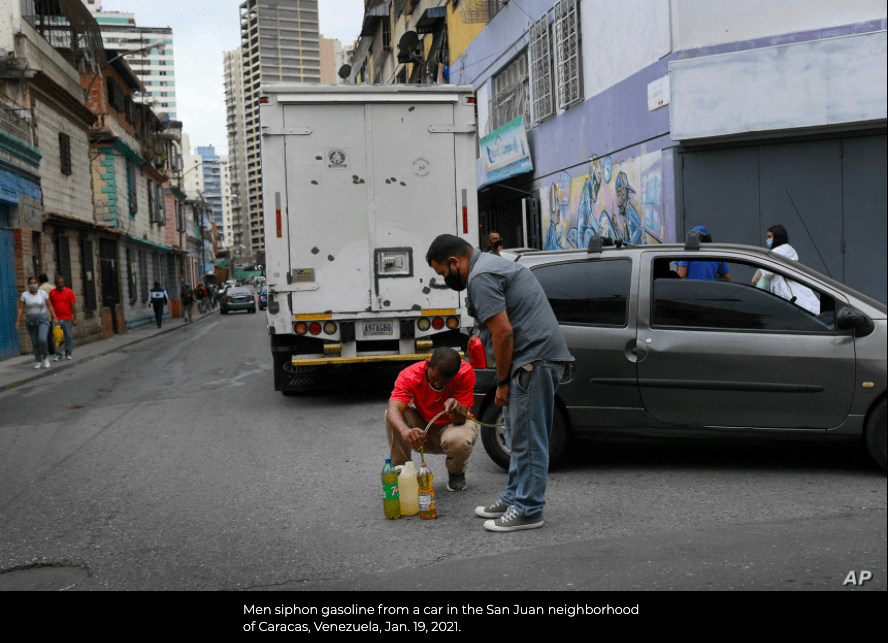

“Every day the situation with gasoline gets worse. In Caracas and the central region of the country, the issue is a little easier. Here we have more lines, people wait four or five days in lines to pour gasoline. General transportation runs on diesel,” he told VOA.

Aliam, president of the “Central Unica de Transporte de Zulia,” confirms that many drivers invested in adapting the engines of their vehicles to use diesel, due to the constant lack of gas.

Venezuelan traders also acknowledge that they feel the impact of the lack of diesel. Felipe Capozzolo, president of the National Council for Commerce and Services, said on Wednesday that there has been no “continuous flow” of liquid hydrocarbon since the end of October of last year.

In a virtual press conference, he specified that there are Venezuelan states that “have the leading role in calamities,” such as Zulia or Barinas, but he warned that the problem already reaches national dimensions.

He expressed hope that this period will be a “lesson learned” for the sectors involved to “generate all our diesel without depending on anyone.”