WRITE-UP | Truncated education | A disjointed educational system

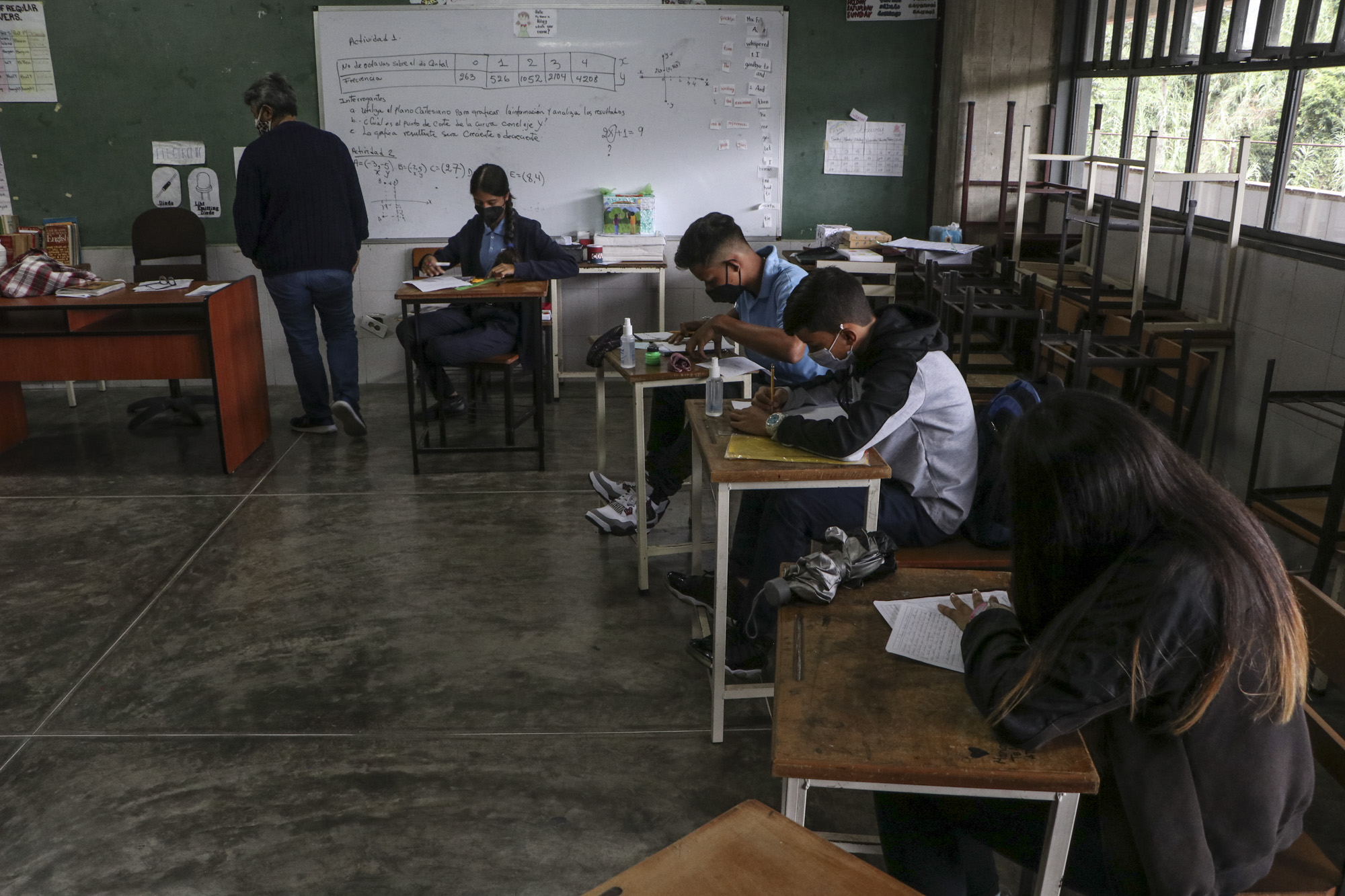

HumVenezuela, January 2022. – Infographics: María Alejandra Domínguez | Image: Daniel Hernández

Planning stoped being a core instrument in Venezuelan education. Chaos has been installed in every instance of the educational process and experts agree that neither the MPPE, nor the governorates, nor the mayors are in a position to guarantee education.

98.43% of the public budget managed by the Venezuelan state was allocated to the National Executive Power in 2022. This data gives an account of the centralization with the given public decisions and the lack of capacity of the rest of the powers to give answers to the population, with the autonomy and in accordance with local contexts, to have internal balances to enforce the compliance of the constitution and the laws, to combat impunity in the face of abuse of power, and to guarantee the human rights.

In addition, for more than five years the State has not presented the annual budget projects, nor is it known on what and how the resources are spent, because the memories and accounts are not public either. For quite some time, there have been huge distortions in the management of public resources. The annual ordinary public budget represents only 1% of state spending. The rest comes from additional credits that are added during the year, executed by the Executive on a discretionary basis, without controls from other public authorities.

According to data collected by Transparency Venezuela (TV), in the 2022 budget, resources equivalent to 15.33% of total spending and 27.61% of social spending were allocated to education, and although it cannot know what the final expenditure will be, this allocation is below 20%, recommended by UNESCO. The budget deficit in education intervenes in the enormous failures of the educational system, but it is only a symptom of a process of destructuring the institutionality of the system. Without a budget, the State owes a huge debt to the educational basket, a term that designates what is needed (and should be free) to guarantee access to education, in terms of registration and monthly fees, school supplies, uniform, food and transport.

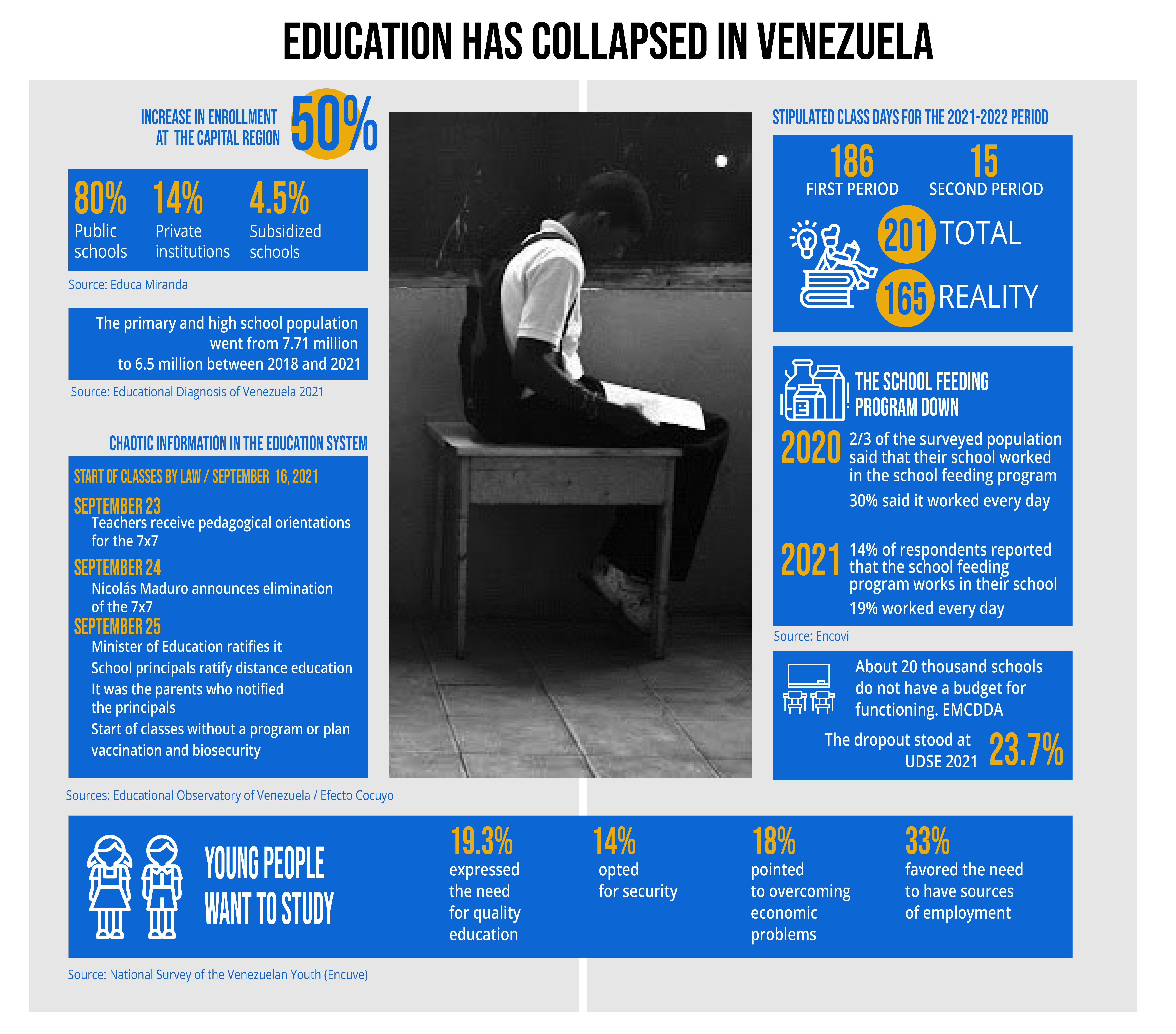

That is why, both Anitza Freites (expert in demography and coordinator of the National Survey of Living Conditions – ENCOVI) and the urban planner Olga Ramos (specialist in educational public policies and member of the Education Assembly), agree to talk about exclusion and not school dropout. The students do not return to the classrooms of their own free will but because the system does not guarantee decent living conditions for children and adolescents (NNA). The school is not able to protect and retain them. “Terms such as abandonment or desertion attribute to the person who leaves the studies, or to his family, the responsibility for that decision — explains Anitza Freites. That responsibility is not only of the household but also of society, because social policy should also intervene so that no one is left behind, incorporate those families into some program and that this is not a reason for exclusion.”

By constitutional mandate and in accordance with international human rights standards, it is the State that has the responsibility to guarantee coverage and access to education. The Ministry of People’s Power for Education (MPPE) — says Olga Ramos “ “is not in a position to guarantee education. We are with a failed education in a failed state. The governorates and the mayors do not have a budget and neither does the MPPE. The national schools do not have how to guarantee the functioning of the schools, including maintenance, hiring of teachers, materials, school food plan. Many regional and municipal institutions have been recentralised – rather than decentralised – for lack of resources. There are numerous municipalities that do not have money to manage their schools and the MPPE does not have funds to manage about 20 thousand schools. In 10 states, the transfer of all educational personnel to the MPPE payroll was carried out.” These resource deficits and recentralization – Ramos comments – produce wide territorial and socioeconomic inequalities, which have an impact on the quality and access to education.

The report 2019-2020 of the Democratic Unity of the Education Sector (UDSE) points out that: “The exclusion from school express features multifactorial, as there is a combination of reasons that the education system itself exclude the student, including the deterioration of the school feeding programme, the reduction of the number of teachers and their conditions of life, the decline and dismantling of the school infrastructure, and the spray of the family wage. Therefore, school exclusion originates from a State that does not assume its responsibility to preserve the right to free and compulsory education. This is what has led to the widening of the gap between those who can access education and those who do not have the means to do so.”

No information about school enrollment

Registration refers to the number of entries in each period of school activity, but in Venezuela the numbers announced by the State do not have to CHILDREN no longer attend, by exclusion, or abandonment, and those who migrated with their families or alone outside the country. The official enrolment figures also do not give an account of the irregularity of attendance or of the CHILDREN who withdraw at some point during the year, temporarily or who do not return to classes for the rest of the period. Previously, absences could lead to the loss of the school year, but with the reforms that the State has made to the rules, CHILDREN can continue even when they do not have the skills of the grade – comments Alexis Ramírez of Excubitus DHE.

The researcher of the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), Nacarid Rodríguez, recalls that, since 1999, the presentation of enrollment statistics in the school system has been losing. Gradually “the memoirs and accounts of the Ministry of People’s Power for Education (MPPE) contained less information than the previous ones, some indicators disappeared, others retained the name, but were calculated differently. More general, less disaggregated data were presented, the information by municipalities disappeared, contradictions between different sections began to appear. So far, the most important thing for the government has been to highlight the enrollment or enrollment data, leaving the real attendance data hidden.”

Drop in educational coverage and quality

Coverage, on the other hand, refers to the scope of the educational system and answers the question of whether there are schools located throughout the country with the proximity, in number and with the amount of sufficient places for the school-age population residing in the area. According to the data collected at ENCOVI, Venezuela has a drop in educational coverage at all ages, but especially in basic school, from 3 to 5 years of age, reported Anitza Freites.

Olga Ramos explains. “In Venezuela that doesn’t happen — he says, teachers and students sometimes have to walk an hour to get to school, because there is no public transport. In Amazonas, if there is no gasoline or rock, they have to row. In Petare – a popular neighborhood located to the east of the capital — you have to go down and up hundreds of stairs to get to the school. All this invites the relationship between the student and the school to be interrupted. If a student has to travel a long way to get to school, the State must guarantee school transportation or student passage. There must be a mechanism that saves them the cost of transportation or travel time, and in Venezuela there is no school transportation system or student ticket subsidy””

In addition, even if the school is nearby, the quality of the educational process is not guaranteed. Ramos details, “There is a zoning of schools, but they are not necessarily close to all towns, and if they are close there may not be an incentive system in terms of the quality of the education they offer. It may be nearby but it does not have graduated teachers, but graduates of social missions, or they do not have up-to-date pedagogical resources, or maybe they miss many classes due to problems with services, or because the teacher did not arrive. Although zoning is a norm, it has been made more flexible by the mess in the system.”

The MPPE, according to Ramos, does not have the capacity to evaluate managers, supervisors or the ability to maintain the entry and promotion process or maintain a standardized education or guidelines that allow schools to have a unified educational, administrative and content management. In the 2021 edition of the National Youth Survey (NVE), carried out by the UCAB, 19.3% of respondents expressed the need for quality education, above security (14%), and overcoming economic problems (18.7%). 33% opted for the need to have sources of employment. It means that in Venezuela the youth is aware of the importance of education as a way of progress.

The sharp deterioration of educational quality is associated with the retirement of a large number of teachers. It is estimated that more than 50% have withdrawn from the system, due to the insignificant salaries, the indoctrination imposed on educational contents and the reprisals to which they are subjected if they question them. The teaching salary is below the poverty line, which has led to a stampede towards other trades to earn a living, even if they are not commensurate with the levels of training. The Funda Redes 2021 report warns that 55% of the teachers surveyed said they were out of the system. In addition, 95% of those who are employed in the MPPE do not have health insurance.

Ravages of the COVID pandemic

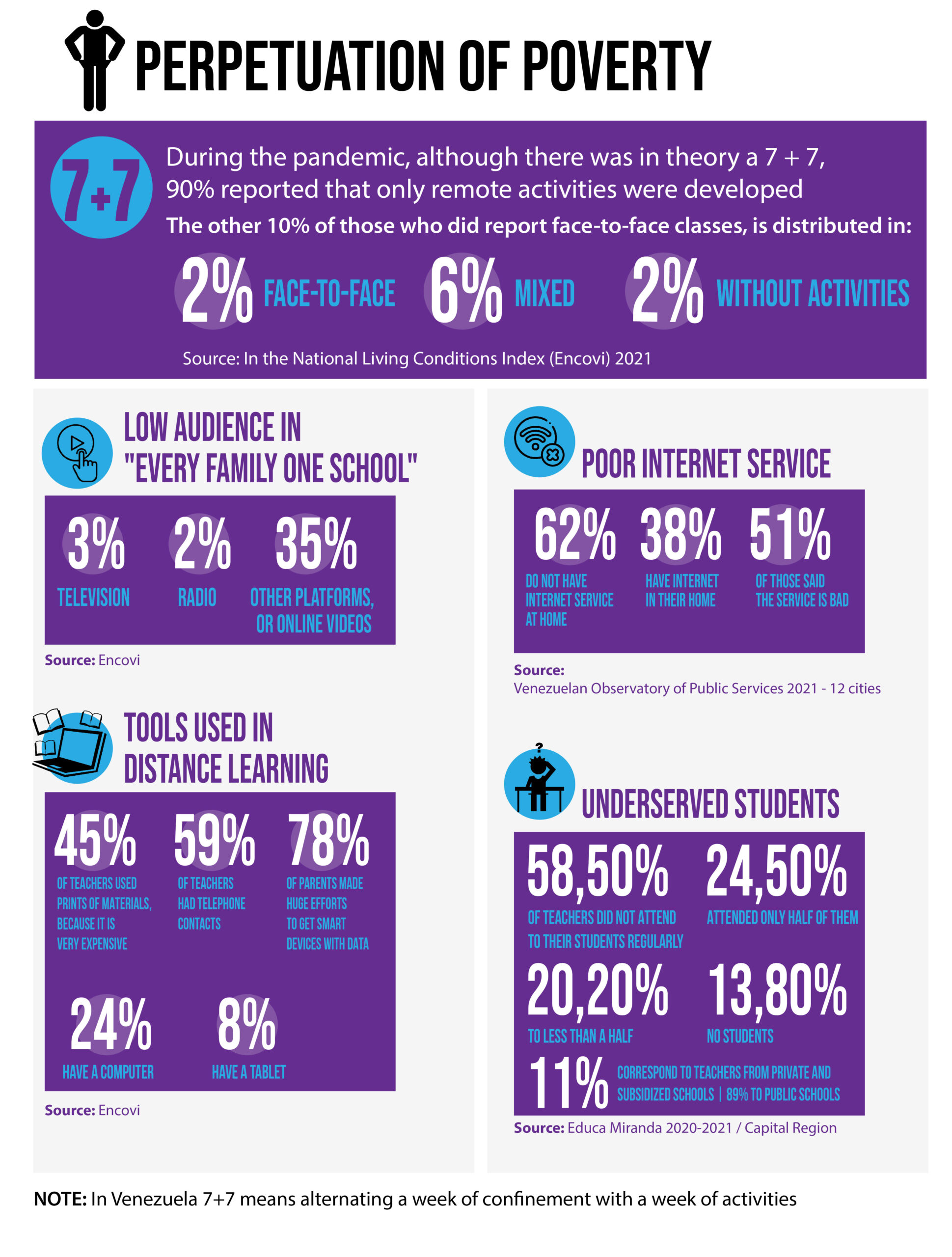

During the pandemic, the destructuring of the educational system was reflected in distance classes without a program, regularity or connectivity conditions to carry them out. In Venezuela, more than 60% of the population does not have Internet at home and those who have the service face a very low connection capacity. Although mobile phone coverage is high, communication problems are frequent due to the irregularity of electricity services. In these circumstances, the One Family One School plan implemented by the Executive during the pandemic failed to meet even the minimum standards of a planned, adequate and continuous teaching process. In part, because the responsibility for taking on a large part of the process was transferred to the families without any support during the time that the suspension of classes lasted. In most households, economic incomes were eroded, there is a multidimensional poverty that affects more than 60% of the population and basic services, such as water, electricity and gas, collapsed.

In the context of the Complex Humanitarian Emergency, the home is not necessarily the best environment for education. Families do not have how to take on more burdens, they do not have the training or pedagogical resources to accompany students. They didn’t even have the technological resources at home, as the plan suggested. In the 2020 study on citizen perception of the Venezuelan Observatory of Public Services, in 10 of the main cities of the country, it was identified that 32.6% of the surveyed users claimed to have lost the internet service at home and 44.4% of these people claim to have presented total loss of their connection in the last 23 months. Among the cities that stand out for the number of users who have lost this service, there are: Maracaibo (47.4%), Punto Fijo (44.0%) and San Cristóbal (36.7%). On the other hand, those that have been less affected were Barinas (16.5%), Porlamar (27.7%) and Barcelona (28.5%).

In an April 2020 statement, the Democratic Unity of the Education Sector (UDSE) expressed that this plan was made in an improvised way. “On the State television channel (VTV), a series of contents were broadcast where it was observed that there was no preparation for classes. The representatives have complained because they cannot help their children enough, they say they do not understand what is transmitted. It insists on the behavioral and not on the reflection and understanding of values. The government forgets that there is not enough internet in homes, others do not even have the WhatsApp application or smartphones or computers, among others.” After a year of pandemic, in another statement of April 2021, the UDSE also highlighted that, in relation to distance education during the confinement, “the right to education was not guaranteed”. The pandemic exposed the situation of destructuring in which the school system is. Consequently, each School Family found more than 1 million CHILDREN “that poverty took out of the educational system” and that we do not know if it will be possible to recover.

Educational programs without content

Before the collapse of the educational institutions, the system had study programs, “and it was known what a student should learn in the first grade, or in mathematics in the second year of high school,” explains Ramos. Today we are talking about generic guidelines, which lack a description by objectives and competencies. However, “this does not mean that the system was made more flexible, but that it was restructured. It lost content. In the general regulations of the Organic Law on Education it is said that modifications can be made to the calendar or to the contents when there are extraordinary situations, but for that it is necessary to promulgate a resolution. In the context of Covid-19 there was no such resolution.”

In terms of time use, the system is also unstructured. There is no longer a school calendar where certain activities are stipulated and in certain periods. Until 2019, more than 60% of the school days had been lost, out of the 200 regulatory ones according to Venezuelan law, due to permanent suspensions dictated by the MPPE, without reasons or a reasonable justification. At the beginning of the 2020-2021 school period, which began in October 2019 and before the temporary closure of schools, 26 days had already been lost.

The 2021-2022 school year was due to begin on September 16, 2021 and end on Friday, July 29, 2022. According to article 54 of the General Regulations of the Organic Law on Education (RGLOE), the period begins on the first working day of the second half of September and ends on the last working day of July of the following year, “but with the late and impromptu start of classes of the 2021-2022 school period, almost a month of classes was lost — explains Olga Ramos. In addition, the distance modality had already disrupted the pace at which pedagogical objectives are met”. But, even so, the MPPE will not extend the calendar of activities to compensate for these absences, so you will barely have 165 days of classes, or less.

To that are added the five days that the campuses stopped working due to the November elections, between the 15th and the 22nd of this month, according to the MPPE. And all this irreparable loss of classes is a consequence of the fact that the Ministry did not get ahead of planning the return to face–to-face classes in the 2021 – 2022 school year, even when the norm says that it should be planned at the end of the previous year. Although it was not decided, had to pre-empt this scenario, considering the fact that in the classes distance with the pandemic, 47% of students learned less, deepened the gaps between students in rural and urban areas, as recorded in the Diagnosis of basic education in Venezuela: Final Report of September 2021: “therefore, it is imperative to invest in infrastructure, basic services, feeding programs and school health to prevent the desertion of teachers and students, and implement programs that foster fluency reader”.

A steep and long slope

The return to classes was not even prepared with clear procedures for the educational system itself. Anecdotally, on September 24, 2021, the Presidency of the Republic announced the return to classrooms on a national network, information that the MPPE reiterated on the 25th. But, the school principals sent the teachers a Whatsapp message — which in turn they had received from their supervisors — in which they announced that the next week there would be confinement and therefore there would be no class. It was the parents who informed the teachers – by Whatsapp too – that education would be made more flexible.

The instructions, orders and decisions in Venezuela are communicated through radio and television networks, and social networks and this is a sign — and a consequence — of a body without structure. As Ramos relates: “The MPPE gives a normative instruction, or guidelines, as they call it, that go to the educational zones, they communicate them to the supervisors, all through Whatsapp messages and not through documents. The ministry produces information that begins to travel the communication channels and is lost along the way. You have a destructuring in terms of communication. And it’s not just that the information channels are informal, but that the information is of poor quality. These misunderstandings would be avoided if the ministry had established the guidelines by means of a resolution, as ordered by the General Regulations of the Organic Law on Education, but there are no formal communication channels, and in addition to these, there are national, state, municipal and autonomous educational institutions in the public system, and even regional ones where there are single authorities. That single authority sometimes has guidelines that are not the same as the ministry, and that cake has no structure or logic.”

How to restore the Venezuelan education system

In the consultations carried out with different civil society actors and specialists in the educational field, the following proposals appeared:

- The right to education must be the focus of real policies to urgently recover the institutionality of the educational system. It is necessary to redesign education in terms of an approach to international standards of law. The study plans must be duly discussed and approved according to what the development of the country is wanted to be. In particular, it is necessary to focus on improving teachers’ salaries and working conditions in order to guarantee education and the quality of teaching.

- A public and transparently managed budget is required to resolve deficiencies in curricula, training and the number of teachers, and to rehabilitate existing schools, in order to guarantee universal coverage of all CHILDREN from 0 to 17 years of age, making equitable efforts so that states and areas with the greatest problems can have access to quality education, on equal terms.

- It is necessary to implement a plan to rehabilitate the physical infrastructure and basic services of existing schools and provide them with innovative pedagogical resources, to bridge the technological gap and rebuild the teaching-learning process. To make schools a model that awakens the need to improve the quality of life and the hope of achieving it.

- Also, it is essential to have access to public information on educational matters, with a real diagnosis of enrollment, the lack of teachers and the situation of schools. A fundamental task is to renew the census of all CHILDREN of basic education age, to find out if more schools need to be opened near their homes and if it is necessary to implement various educational modalities to reduce the levels of backwardness.